Hong Kong from the Peak.

We decided to sail for three days with the ship from Hong Kong to Shanghai. By sailing with the ship, Jo was deprived of a trip to the Great Wall of China, but for the two of us to have made that journey would have cost more than a thousand dollars. I’ve been to the Great Wall four times already, one of them last summer, and while it is a great Great Wall, I was more interested in the two days in Shanghai where I’d never been before. Neither of us had ever been to Japan, and our friends were lobbying for us to join them in Nara and Kyoto. So we spent two days in Hong Kong, had a quiet three days sailing on the ship with the hundred or so of us too broke to fly around China, and then had two days in Shanghai.

Hong Kong is one of my favorite cities. This was also the first time I’ve ever been to Hong Kong when it wasn’t dreadfully hot. In late May, the tourist is dependent on Hong Kong’s over-achieving, and ubiquitous, air-conditioning. Walking outside of your hotel in the morning is like moving from a freezer into a bowl of pea soup; your glasses steam up. On this trip to Hong Kong, however, it was early spring, cloudy and grey---sweater weather. The air-conditioning was gratuitous, and sometimes not on at all. It reminded me of when Eileen Kaufman and I made our first trip to Delhi in December, having been there many times before, but always in June. In June, the night air in Delhi is like a tandoori oven. In December, the night air in Delhi is cool and crisp, and full of the fragrance of jasmine. What a difference 30 degrees Fahrenheit can make.

Jo and I made a deal in Hong Kong: she’d go her way with her friends, and I’d go my way with mine. The poor thing---four days alone with her very sick mother, trapped alone in a hotel room in Bangkok, has probably scarred her forever. Besides, since February, she’s part of a protean group of college kids, and I knew that she’d have more fun exploring Hong Kong with them. I spent my first day with our friends Joan and Bill, both faculty members, and we did all the touristy things since Bill had never been to Hong Kong before. That was fun for me, and truth to tell, I hadn’t been up to the Peak on the cable car since 2000. The view was still stunning, but the entire area around the Peak has been enclosed, and made into a multi-storied mall. This meant that you couldn’t get outside on the Peak without purchasing a second expensive ticket, so we decided to eat in one of the high-end restaurants that had a view. Just what Asia needs, we grumbled, another multi-storied mall?

Aesthetically, the malls of Asia put ours to shame. They have eight and nine stories, shiny marble floors, polished brass railings, glass-encased, neon-lined escalators, indoor fountains and creative landscaping, and pristine bathrooms with an amazing array of hand-drying machinery. I suppose too, there’s shopping. Actually, we didn’t shop in the malls of Asia because we can’t afford to. Jo and I used the malls as palatial pit stops, and perhaps for the urban Chinese in particular, the mall is a kind of palace---except in this case, the palace is not Forbidden; it is open to all. All are free to window shop at the mall, and in the muggy summer, to enjoy the air-conditioning. Indeed, that may just about sum up the individual freedoms in China. Don’t get me started…

Ok, just to be clear: I am not proposing that our students should only visit the malls of Asia, but they can be a lot of fun.

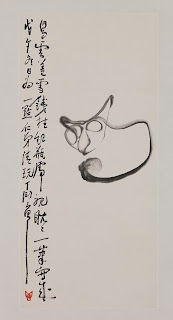

On our second day in Hong Kong, Jo and her friends took off for Stanley Market, and I spent the day alone, my second day of blissful solitude in almost four months. I walked up and down Nathan Road, had lunch in Kowloon Park and watched geriatric tai chi, and spent most of the afternoon at the Hong Kong Museum of Art. I never miss a visit to this museum because it has one of the best book stores in town. (I’m usually on the hunt for books in English on Chinese art and culture.) On this trip though, I lucked out with the art. The exhibit was of the paintings of Ding Yanyong (1902-1978). Ding was from Guandong, but had studied modern art in Tokyo in the twenties, and later became a part of the western painting movement in Shanghai, adopting a style reminiscent of Matisse. In the 1930s, he became interested in traditional Chinese art, and from that time on, his work synthesized the art of the West and the East. I particularly loved his ink on paper scrolls, and the playful one-stroke paintings that he did as an old man. The museum played a film on a loop from the 1970s of Master Ding performing these later paintings, and interacting with his students who were oozing filial piety. I watched it three times, all alone in a dark room, collapsed on a museum sofa. His personal life was tragic. Ding migrated in 1949 to Hong Kong, leaving behind his wife and four girls; he was never reunited with them. All of his art work in China was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution; his family was sent to re-education camps as “feudal bourgeoisie.” Living a bare-boned existence alone for years in Hong Kong, he was alienated from his country and from his family. Even Ding’s humorous, satirical pieces---of which there are many---betray a palpable loneliness.

Hong Kong's laser show.

The MV Explorer at night.

The Bund Sightseeing Tunnel.

I only have Beijing to compare Shanghai to, and let me say this: Shanghai is not Beijing. Beijing is laid out in a predictable, rational design; Shanghai is not. It’s difficult to navigate, and none of the city maps makes any sense whatsoever. Beijing is international and cosmopolitan; Shanghai feels more parochial, and is distinctly Chinese. Its population is far more homogenous, and I was impressed by how big the people were, many over six feet, with broad-faces and eyes that looked quite different from the eyes of Beijing. Beijing has many stunning tourist sights, but the rest of the city was torn down to make way for rows and row of monotonous, shiny glass boxes. Shanghai has very few stunning tourist sights, but has preserved its historical heritage. The Bund, and the French Concession, are stunning, and south of the Bund, you can find something that no longer exists in Beijing: an Old Town. We spent several hours in that Old Town, walking through the maze of narrow lanes, ducking under laundry hung in front of and between the closely packed houses, dodging bicycles, our eyes stinging from the smoke of small, local temples and open fires where food was cooking right on the street. I much prefer Shanghai to Beijing, and look forward to spending more time there. If I never went to Beijing again, it would be just fine with me.

Shanghai's Old Town.

Representatives from the community center.

I was sad to spend only those few days in China. China has grown on me. The first time I went to China and lived in Xiamen for a month, I found it fascinating, but it did not call my name---not the way India does. India is a large, rowdy democracy where anything goes, and often does. China is a totalitarian state. Censorship keeps their population ignorant of their government’s policies, and few feel free to speak out. On a tour of Tiananmen Square, one of our students asked how many were killed in 1989 in the military’s forcible---and deadly---dispersal of student protesters, and the young tour guide responded, “Oh, not so many as they say, only a few. Most of those photographs you see are ‘photo-shopped.’”

That answer makes me weep. The Chinese government has “photo-shopped” their recent history, their record on human rights, their appalling excuse for a criminal justice system, their planet-threatening pollution, their repression of religious groups who threaten their authority, their rampant consumerism and energy consumption, their myriad intrusions into the lives of their citizenry---uh oh, you got me started.

But I’ll stop. The truth is: Regardless of how I feel about the Chinese government, I still have a deep affection for the Chinese people, for the perpetuation of their ancient culture under extreme adversity, for their industry and tenacity, and at least in my dealings with them, for their great kindness.

The students at Semester at Sea have experienced a lot of anti-American sentiment as we’ve traveled around the world. We’ve talked about it repeatedly in our “Post-port Reflections.” To have someone in a foreign country blame you personally for our war in Iraq (which you didn’t support) or for dropping a bomb that killed 90,000 civilians (when you weren’t even born yet)---those accusations hurt. Some of the students have responded with anger; some with shame. Here is where travel educates. You learn to distinguish the people from the government. It’s possible to love one, and not the other. By someone covering you with a careless stroke of a brush, you learn to paint your own canvas with more care. LH

I had not visited Hong Kong, but i will definitely say from the above pictures that it is very beautiful.

ReplyDeleteI really enjoyed reading about China. The final paragraph is very incisive. At times, I have experienced similar anti-American sentiment abroad. The comments sting but, after I've recovered from the surprise, I emerge with a more nuanced understanding of the world. I'm looking forward to seeing you soon! ~ James

ReplyDelete