Cherry blossoms in full bloom.

The ubiquitous old ladies of Japan. On the streets, in the marble malls, on the trains, and in the parks, they were everywhere, teetering around in Minnie Mouse shoes, wearing woolen suits with long, slender skirts, and matching tailored jackets, printed silk blouses showing shyly at the collar. Many sported hats, some elegant with silk flowers demurely attached to a satin ribbon that circled the base, some utilitarian and discordant with the rest of the sartorial splendor, oddly reminiscent of what my father used to refer to as “old man fishing hats.” Their faces were perfectly painted, with ruby lips creating a bow, salmon-colored cheeks, covered with white powder; they looked like apparitions. Frail, thin, these old ladies of Japan looked as if the smallest breath of spring wind might blow them away. They reminded me of the fragile pink petals that had already pulled off from the sap of the cherry tree, waiting for a nine-year old boy to shake the branches just to watch the velvety snow to fall.

That is one thing I noticed immediately in Japan: there are lots of old ladies, and very few children. Indeed, the birthrate is very low; one of our guides told us that each woman might be expected to produce only 1.3 children. She also told us that many professional women in Japan choose not to have children because they impede the development of their careers. Many of those same professional women end up living in apartments with their aged mothers. Housing is brutally expensive in Japan, and their aged mothers need them. I saw those duos everywhere: a middle-aged woman wearing a dark business suit shepherding her mother through the crowds. One of her arms was burdened with a briefcase, and the other with a wraithlike mother, turned out to perfection. A sturdy crow in designer glasses, with an elderly, delicate sparrow on her wing.

The toilets in Japan were utterly wild, and not only carried out this theme of cleanliness, but suggested a national obsession with private functions. In the hostel that we stayed at in Nara, sleeping in a communal room on tatami mats with some Semester at Sea friends, there was a toilet that was so high tech, I had to fetch Jo to show me what to do. The seat was heated, and had a dial that regulated how hot you wanted to bake your butt. (This feature was terrific; how primitive our chilly toilet seats on the ship seemed when we returned.) There were two different sprays of water that one could select, depending upon what geographical region you were aiming for---a whale spout effect from down below, and then another stream of water that came at you directly from the rear of the toilet. These too had dials that regulated the strength of the streams. Then there was a dial for what turned out to be the equivalent of a hair dryer for the general region, presumably to evaporate all the warm water. (This feature was alarming.) When you were duly dried, you were supposed to push the button that said, in English and Japanese, “Super Powerful Deodorizer,” that blasted you with some sweet smelling noxious chemical that I disliked enough to start pushing all the water spray buttons once again. My favorite of all, however, and a feature in almost every public toilet I used in Japan, was a button that masked the sounds of one’s elimination with either a faux flushing sound, or the sound of a rushing waterfall.

I was totally fascinated and repelled by Japan. The cities were ferociously dense in population; the train stations teemed with well-mannered, well-groomed, efficient, restrained, obedient, hard-working, and distant people. Of course, I generalize. Many acts of kindness, complete with full waist bows, were showered upon the bumbling, illiterate Americans who couldn’t figure out the Byzantine railway system. Courtesy abounded, but Japan offered none of the warm embrace of India, none of the sweet, shy curiosity of the Thais, none of the open-heartedness of the Vietnamese, even any of the rough and ready---but always friendly---brusqueness of the Chinese.

The streets of Tokyo.

Perhaps it was the documentary I’d seen the week before on the Hikikomori children that colored by perceptions of Japan. The term “Hikikomori” means “withdrawn,” and applies both to the social condition and to the people who suffer from it. The Hikikomori are adolescents, usually male, who collapse under the pressure to succeed in school, to be the best and the brightest, to fulfill their family’s high expectations---they fall apart and refuse to leave their bedrooms for months, sometimes for years. They sit in darkened rooms, and surf the internet and play computer games. Our Japanese lecturer on the ship told me that she knew two Hikikomori who haven’t been out of their bedrooms for over a year. One of the families is so ashamed of their son’s withdrawal from society that they have told everyone he’s studying in the United States. He is violent towards his parents, and only comes out to go to the bathroom; they feed him by leaving trays of food at his door. The other child has been living for awhile in a half-way house for Hikikomori, slowly coming out of his self-imposed exile. There are some instances of Hikikomori in Korea and in China, but it is mostly a Japanese phenomenon. As I walked past groups of young Japanese men in the train station, wearing tight jeans and black leather jackets, their hair dyed red or blonde, in a style reminiscent of Rod Stewart of yore, I’d ask myself: Who are these children? And what kind of culture creates a social category like the Hikikomori?

Part of my problem with Japan was me. I’m not a big fan of shame, and in Japan, the avoidance of shame motivates a great deal of behavior. I would see commuters on the train, perched circumspectly, anxiously on the green velvet seats, and I wanted to lunge across the aisle, grab them by the lapels, shake them, and yell, “Smile! Whatever it is, it’s not so bad. You’re doing just fine, or at least good enough. Don’t be so hard on yourself. Stumble on a little joy. Have some fun!” Of course, I just sat there in silence, but my repressed outburst worked its way down into my very core, and before you knew it, I’d be sad and depressed. I’m not sure Japan and I could spend a lot of time together.

We did have a magical day in Nara. The weather was splendid---a little chilly, but sunny, and the cherry blossoms were in full bloom. A whole group of Semester at Sea families arranged to travel a few days together, and we generated our own fun and our own joy. The first capital of Japan, Nara is famous for its free-ranging deer who stroll through the city parks, begging for food, and posing for photographs. It was molting season, so their coats were uneven and patchy, but they had such sweet, trusting faces, and I loved the confidence with which they walked among us. We did most of the sights in Nara, but my favorite was the Todaiji Temple, the largest edifice in Japan, and one of the oldest, having been built in 743 C.E. Perhaps it was the sweetness of the deer faces, but for some reason in the Todaiji Temple, I was feeling very sad about the loss of our cat, Sweetie, right before we left for Semester at Sea.

The deer at Nara.

Jo feeds a deer.

You may wonder how the loss of a cat relates to Japan, but it does. Sweetie had been with us for about ten years. She was never an easy cat. Beset with medical issues, a constantly snurfling, snot-laden nose, obsessive compulsive licking, the shivers and shakes, Sweetie was a trial. For a decade, she dominated our household, with her bed on the sofa, her kitty heat lamp, her constant supply of hot water bottles because she was always so cold. But that said, Sweetie was the only grateful cat I have ever known. Cats usually approach the world with a sense of entitlement, but not Sweetie. She knew that she was a burden, and she lavished affection upon us. It was impossible not to love her. And then one day in October, she took a stroll out onto the driveway, and disappeared. Nan and Jo scoured the neighborhood, put up flyers, registered her at the pound, but to no avail. Sweetie had vanished into thin air. The vet opined that a hawk had taken her. Hawks were in the neighborhood that week, and had made off with a number of small pets. We were utterly devastated.

Anyhow, the deer in Nara reminded me of Sweetie, and I was feeling blue. Then our friends, Bill and Joan, told us about a program at the Todaiji Temple. The priests were raising money to replace the roof, and for ten dollars, you could buy a roof tile, and with a brush dipped in black ink, dedicate the tile to whomever you pleased. Bill and Joan were going to memorialize their beloved dog, Sabaii, a soft-coated Wheaton Terrier who had lived with them for fifteen years, and had died in 2007. We loved the idea, and decided to claim the tile next to theirs so that Sabaii and Sweetie could hang out together in pet heaven---surely located somewhere in the eternally blooming cherry trees above the roof of the Todaiji Temple. It was our way of saying goodbye to Sweetie, and we signed the tile “Louise, Nan, Kate and Jo” for the sisters who were also mourning her loss. Sweetie was a very maternal cat, and would surely lick Sabaii’s head, and he would, we were assured, valiantly protect her. I would never have anticipated that we would lay Sweetie to rest in a Buddhist temple in Nara, Japan, but we did.

A priest at the Todaiji Temple in Nara.

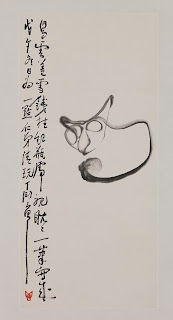

Our memorial to Sweetie in the Todaiji Temple.

We did so many other things in Japan in the nature of seeing sights: Kyoto, also in full cherry blossom bloom, and Tokyo. The former was lovely; the latter overwhelming. We took a full day tour of Tokyo, and aside from a visit to a really stunning Shinto Shrine built in the 1920s, the Meiji Shrine, it was too new, too shiny, too fast, too impersonal---too much for me. I did grow very fond of the Shinto shrines in Japan. Usually located right next to a Buddhist temple, the Shinto shrines house the indigenous, local gods---the kami---who inhabited Japan before Buddhism was introduced in the sixth century C.E. The shrine itself is almost always surrounded by a quiet woods and pebbled paths; you enter through a large wooden gate without a door known as a torii. The torii marks out sacred space from the mundane, and is meant to purify you from the top down; as your crunch through the pebbles, you are purified from the soles of your feet up. Before you enter the Shinto shrine, you stop at the purification trough and wash yourself in an elaborate cleansing ritual. You clap hands loudly before you go in; you clap hands loudly as you finish your prayer, all to let the kami know that you are there. I loved that the kami had jurisdiction over the day-to-day problems of life: getting a new job, becoming pregnant, doing well on an exam. Nothing was too small to bother a kami with, unlike the Buddhist temple usually looming nearby that was devoted to death and eternity. Shinto shrines were all about the business of living, and we saw many Japanese couples bringing their newborn babies to be introduced to the kami. Outside the shrine, you could buy amulets and other trinkets blessed by the priests. At the Meiji Shrine, I bought a medallion in a white silk bag to ward off evil, and for all the administrators at Touro, I bought a “success pencil,” guaranteed to bring good luck to its wielder. Everything was open in the Shinto shrines; you could never tell if you were outside or inside, or somewhere in between. That was true of much of the architecture. Subdued, elegant, organic---the aesthetic was the best feature of Japan.

The wash basin outside a Shinto temple.

Priests inside a Shinto temple.

I wish I had loved Japan more. If I understood why I didn’t love Japan, I might know more about myself. My response wasn’t due to any lack of beauty, that’s for sure. Maybe some day I’ll return, and be able to see Japan through new eyes. Maybe I’ll find something there to compel me, or to pull at my heart. Nara---now there’s a place I’d love to visit again, and of course, I’ll have to go back to pay homage to the spirit of Sweetie, and her faithful companion, Sabaii. LH

Jo in Yokohama.