But the fact was: I didn’t much like Oahu. It was physically stunning. We took a day-long tour of the island, and saw beautiful beaches, aqua blue water, palm trees, coral reefs, blooming flowers, and the scene at Waikiki. But everyone walking along the street was loud and large; everyone was American. We were spending dollars again, and lots of them. The entire island was devoted to the pursuit of pleasures that I don’t take much pleasure in: eating meat, drinking alcohol, baking on a beach, surfing. After months of being in foreign environs, of struggling with other languages and different ways of life, we were suddenly back on U.S. soil, even if we were floating on an island in the middle of the Pacific. The consumption was conspicuous. I wasn’t ready to be home.

One morning, we went out to Pearl Harbor to see the memorial to the USS Arizona. It was moving, although after Japan, my mind was full of the war memorial at Hiroshima. All I could think about was how surgical the strike on Pearl Harbor had been. How solicitous the Japanese had been of civilian lives, and how cavalier we had been when we took our revenge. 140,000 civilians were killed by the bombs in Hiroshima; most of the city was wiped out. At the USS Arizona Memorial, we only mourned the loss of 1,100 or so American sailors who’d been trapped beneath the sea; only 68 civilians were killed. Those numbers seemed small to me. The fact is we care more about dead American sailors than dead Asian civilians. Just as we rail against the 4,000 plus American soldiers killed in the Iraq war, we ignore the fact that over 80,000 Iraqi civilians have been killed. Is it human nature to privilege the deaths of our own? Is there something wrong with my nature?

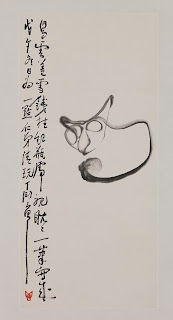

Memorial at the USS Arizona.

Street scene in Antigua.

The ubiquitous rifle.

We spent most of our time in Antigua, the Spanish colonial capital of Guatemala, and now a designated World Heritage Site. Most of the architecture in Antigua is eighteenth century. Even though the city was founded in the middle of the sixteenth century, a great earthquake destroyed it in 1773. Its focal point is the broad, tree-lined Parque Central, a broad and beautiful plaza with many wooden benches from which to watch the Antiguenos, the tourists, the hawkers, the artists, and the Spanish students strolling in or through the park. In the center is an outrageously tacky fountain, a 1936 reconstruction of the original 1738 version, complete with concrete nymphs sporting breasts that spewed water. On the east side of the park is the Catedral de Santiago that has been demolished, damaged by earthquakes, wrecked in the last eighteenth century, and then partly rebuilt in the nineteenth century. It looks best lit up at night, as is true of many old, decaying queens. Three blocks away from the park is the Arco de Santa Catalina, built in 1694 to enable the nuns to cross the street without being seen. There are many other churches in Antigua, ruins of monasteries, remains of 16th century convents and the like. Many of these buildings that were once gilded, baroque treasures are now romantic rubble, having suffered from too many earthquakes and not enough money to restore or maintain them.

Scenes of Antigua.

Mayan women in the market.

The local Antiguan market.

We stayed in a lovely three-story 18th century mansion with tile floors, tall ceilings, roughly hewn beams and wooden windows that opened out onto an inner courtyard. We were able to open those wooden windows which for me was an intense pleasure. One of my few gripes about ship life was the lack of access to soft breezes. I lived in a room hermetically sealed off from the world, with a window that looked out onto the sea and the sky, but with no fresh air. When I sought fresh air on the deck, it came with a blasting, blinding sun and a wall of wind that blew me away. I realized in our room in Antigua how much I was missing a soft breeze, with slanting rays of sunlight on my bed, the sound of a barking dog in the distance, the tinkle of my wind chimes, hanging on the tree outside my bedroom. It dawned on me in Antigua: I was missing home.

Our hotel (and Louise's feet looking out her wooden window).

And so, our Semester at Sea adventure has come to an end. Having been home for awhile, and adjusted to the familiar grooves of our lives, the trip begins to take on a surreal quality---all those foreign places, in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Central America, all those tastes and sounds, those languages, those strange coins, the deserts, the mountains, the horn-honking cities, all that sun and sea, all those wonderful new friends, now here, now gone. It’s hard to know where to put so many memories. I can’t seem to squeeze them into any convenient corners of my mind. Maybe over time, I’ll package it up; maybe I’ll never succeed. Who knows what Jo will make of the whole experience, but of this I am certain: She’ll never be the same.

People have warned me that Semester at Sea can become an addiction. Once is not enough. I believe that. Jo’s already rooting for 2013. I say: we’ll wait and see. But the truth is we’re already plotting. We’re already planning. Half the fun of travel is anticipation.

Someday I expect to be a very old woman, no longer able to navigate the world, and I’ll have the comfort and company of three doting daughters in their middle-age, with little red houses in the woods and children of their own. But Jo and I will always share something that no one else will be privy to---the memory of this remarkable trip. Even now, just one month home, I find myself driving her to school in our Subaru, thinking that we need gas, worrying about whether I’ll be late to work, remembering that I need to pick up milk on the way home, and then I’ll suddenly look over at her and say with dubiety, “We did sail around the world, didn’t we?”

And she’ll nod and give me a secret smile. “Yes, Mom, we did.” And because she says so, I believe her.

LH and JJ

**********

Jo and Louise back home on Long Island.